anonymous

midatlantic

In 2010, I was living in soulless, international student accommodations in Islington, London – right above the MasterChef studio. I tried to make friends with my Chinese flatmates, but they kept to themselves and only came to the kitchen to cook – usually Skyping home to complain about everything.

Class was very much the same. The second-year International Journalism students already bonded over the first year of International Journalism. They kept to themselves and their dictaphones, blogs, and cameras (phones weren’t smart yet) and only came to the lab to upload multimedia content about tuition-related, student-led protests.

There wasn’t very much of a universe outside of the university. People worked there, but they didn’t live there. By 4 pm, it was a grey and miserable ghost town haunted by cranes.

Just a year prior, I was living in Northwick Park – on one of the most creative campuses in all of London. I tried to make friends with my American flatmates, but they kept to themselves and only came to the kitchen to cook – usually Skyping home and complaining about everything.

I was forced to get out of my comfort zone, go out into The Smoke, and assimilate. In doing so, I befriended a Nigerian developer, a Norwegian journalist, a Swindon photographer, a Japanese designer, an East London bassist, a West Country drummer, a South African footballer, a North Wales filmmaker, and an East Anglian illustrator.

Each friendship forged in spontaneity. Car park barbecues. Shopping trolley bonfires. Impromptu snow raves.

I remember everyone making a big deal about the snow, saying it “never snows”. The entire city of London shut down because of it – and it was but a cough compared to the snowstorms of my home state of New Jersey. There, they’d blast the suburbs with salt to get you on the school bus in ninety minutes. Such was every birthday of my teenage years.

I decided, upon my twentieth birthday, that I would start anew and abroad on my twenty-first birthday (a special year for Americans). Failing to demonstrate acceptable levels of French and Spanish after three indoctrinated years, I was left with English-speaking options. And despite watering down the privilege of the twenty-first birthday well before turning twenty-one, London seemed the obvious choice. The pound-to-dollar currency conversion during the recession felt a once-in-a-lifetime discount.

I was accustomed to living out of a suitcase long before this point, but moving abroad meant finally having to let go of my dad’s belongings and opt for existence-dependent identification and all that student loan paperwork (lucky me – no cosigner to curse with foreclosure should I default on repayment).

I remember being jet-lagged, wearing one too many layers in order to hack the weight limitations of my luggage allowance (back then you could have two pieces of checked luggage and a carry-on), and looking for a nonexistent door on the wrong side of the bus. I remember staring out of the window, horrified that dogs and children were driving cars – only to keep reminding myself they were actually seated in passenger seats.

I remember the culture shock of Oxford Street – wanting to keep up with the herd, but not knowing where I was going and what side of the pavement to stand on. I didn’t know where to find the name of the street I was on, or if I was even looking in the right direction when crossing it. I made a lot of people mad standing at a zebra crossing, flagging traffic to continue.

I, too, remember that break-down in Carphone Warehouse, struggling not only with the British accent, but British phrases. And not just the British pound, but British notes. And value added tax. And fair pay-as-you-go tariffs. And the jaw-dropping moment I laid eyes on Big Ben.

After a much-needed nap, I woke up to a different London. A multicultural mecca that won me over with its many, different illuminated buildings, all originating from many, different points in time, and influenced by many, different places – with many, different people, speaking many, different languages, dressed in many, different fashions, coming in and out of them.

I tucked into many, different cuisines, absorbed many different songs, films and plays, and received many, different takes on my very, different country as told by many, different sources. I could finally voice out loud my disdain for the Bush administration. It shocked me that it shocked no one. Especially my first friend in the UK – a DOP from the Rhondda Valley who was more or less ambassador to my new life in the UK. Through him, I learned about the NHS and the G20 protests.

Over the Easter break, I visited his home in the valleys. We walked past the slanted, terraced housing of his street, vanished up into the forest, and sat on the top of a daffodil-coated, sheep-grazed mountain, overlooking a disused quarry, a farm, a neighbouring town, and its graveyard – all in the disconnected quiet that comes with heights.

He found my paranoia funny, having come from a place where land was something owned and not shared. I couldn’t believe we weren’t trespassing and I couldn’t relax because I anticipated the warning shots of a gun. I remember telling him everything was beautiful. And I remember him responding: “That’s because you don’t live here.” But I didn’t understand.

My student visa expired with spring semester. I thought I would have figured out who I was and where I belonged by the end of it, but I didn’t. So, I applied to come back for another semester. And another. And another.

In early 2010, I received an email that said it would be “the last time”. Being the first of my home university to study abroad for this long, they decided to make a precedent out of me by getting together and voting against this being a thing for anyone else. Missing out on third year meant this was goodbye – my star-crossed friends would all graduate at the end of term and go off on their own separate ways into the world.

So, there I was, feeling particularly gloomy, staring over the MasterChef studio. It smelled wonderful, of course, but I was feeling gloomy. Sure, my Chinese flatmate would enter the kitchen now and again to stir a boiling pot, but they might as well have not been there. My friends, a forty-five minute tube ride away and scattered around Harrow, might as well have been on another planet. Once hall mates, second year splintered us into different student houses, meeting only by chance at uni or at a party. My boyfriend, who wanted nothing more than to be a drummer in a rock band, was now enjoying success helped by social media, radio play, the Camden scene, and having a bandmate on Big Brother. This meant being away, unavailable and disinterested.

I thought, if I was going to fling myself off the building, I could at least go out doing something nice like give MasterChef some ratings. An MSN ping stopped me. A YouTube link from my East Anglian illustrator friend. Sigur Ros’ “Svefn-g-englar”.

I realised then, that I made a terrible mistake and was with the wrong person. But the code of bros prohibited me from correcting it. Still, at every concert, he stood next to me. At every party, he sat next to me. After every fight, he drank with me. And when I didn’t feel like talking, we would talk with our instruments. Me through a keyboard. Him through a guitar. “There, There”. I cried the entire seven-hour flight back to the states.

My relationship ended shortly after disclosing I’d pre-purchased flight tickets to visit over the Christmas break. So, I spent it with the East Anglian illustrator who introduced me to a fine city called Norwich and I revelled in being an exotic thing. Three days before I left for the states, I told him I loved him and he said he wanted to see this through. Our long-distance relationship began.

I soon graduated into a US recession. He soon graduated into a UK recession. He didn’t have to pay back student loans until finding employment, but I did (Americans had to repay student loans within six months of graduating, whether they found a job or not). The only loop hole to this was continuing education. I applied to a British university and incurred more student loans to stave off undergraduate student loan repayment. It also meant at the end of my two-year post-graduate course, I could remain in the UK to look for a job. Win-win, I thought.

Long-distance didn’t feel long-distance between London and Norwich. During this time, I learned things I didn’t learn in school. Like my rights as a tenant and the corruption of London landlords. Like living around the corner from where the 2011 riots started. Like the cruelty of the Home Office, who ended that look-for-a-job-upon-graduation scheme in the middle of my course – and booted me, and the rest of us international students, back to our home countries because our classroom contact hours fell below full-time. Long-distance really felt long-distance between the UK and US. More so because were also engaged.

I was homeless. Again. Now with unpaid, good-for-portfolio internships and zero-hour contracts. I worked up to five jobs at a time – most ending with being laid-off (others got sacked for being sick). No one was hiring (no one had five years’ experience for an entry-level role) – and student loans needed paying off (so did a bailout bank account, go figure). Everywhere around me – closed independent businesses, foreclosed houses, and the beginnings of an opioid crisis.

I lived with a friend, who lived with her parents after graduation because she couldn’t find work. Still, I was expected to complete my course with a five-hour time difference, in a recession, with Internet access dependent upon library and Barnes & Noble hours in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy (my lecturer kindly gave me a grace period of one week to catch up when electricity was out for three and then another from a blizzard).

I started an internship at a newspaper publication powered by emergency generators for the remainder of 2012. My editor wanted me to write about luxury handbags and boxers when I wanted to write about the places of my childhood memories – suddenly gone. Haiyan would hit my father in the Philippines one year later.

2012 meant the introduction of a £18,600 income requirement for us, my British citizen “sponsor” and me, the non-EU fiancee, to be together in the UK. We also had to have the same job for a continuous six months (or else reset the clock). If we didn’t, we had to have £60,000 in savings in the bank – left untouched for six months. I thought it impossible and that it was more likely for me to sponsor him to live with me to the states.

When I got my job as a publicist, I met the income requirements stateside. However, I did not have accommodation of my own and would have to wait six months to prove I’d been with the same employer, making a consistent amount of money for that amount of time. Easy I thought – stay employed, find an apartment, and sponsor my fiancé.

Then, my employer paid an unrealistic amount of money to fly a friend of Kim Kardashian’s over to us in the suburbs to attend a rebrand strategy meeting. The cost of him pitching bacon-flavoured diet bars for half-an-hour cost us all of our jobs. I was back to the zero-hour contract, minimum-waged shifts, forking out $900 a month for student loans when I could barely afford to pay my friend’s mother rent, utilities and groceries. I also missed my own graduation.

My fiancé didn’t make £18,600 at his first job upon graduating. Who did? He also didn’t have £60,000 savings in the bank. Who did? We thought it impossible. Long-distance was hard when working irregular shift patterns and living out of someone’s basement. Then, at the zero hour, we were gifted £60,000 in savings from his family. We let it sit in the bank for six months. By some miracle, my fiancé found and secured a job – holding on to what he loved, which was making art (not an easy feat).

We made our application to marry and live together in 2013 – and heard back shortly after my twenty-sixth birthday in 2014, just as I was reunited with my mother. There was no time to assemble wedding plans – let alone secure a date. That had to be done whilst in the UK – registering our intent to marry in another country called King’s Lynn before marrying in Norwich within the window given to us. It gets me every time thinking about bridezillas and their specifications.

I left my mother, sister and home country behind in 2014, in the same week my mother lost her mother (due to not being able to afford blood) and her job (due to the recession). I could not afford to miss my window and reapply. I am still coming to terms with this.

I lived with my retired in-laws with no recourse to public funds and no rights to work. The public did not know that – or care to know. I was ashamed to be exotic. I tweaked my very different accent. I wore long sleeves to cover my very different darker skin and baggy jumpers to cover my very different body shape.

When my fiancé went off to work, I stayed put in his room, feeling guilty of taking up any other space in the house. I was afraid to call home because the rest of the house was around or asleep. It snowed that winter. Everyone made a fuss about it, saying it doesn’t snow in Norfolk. I stopped having birthdays.

The big wedding day itself – as most girls don’t dream – was an office cubicle with my in-laws. None of my own family. Neither of our friends. The whole thing took maybe fifteen minutes. All I remember about it was feeling sad and that our mini-moon took place over an exceptionally hot May in 2014 because it was the first time in my entire life that I actually got sunburn.

When it was over, I still couldn’t work. I had to wait for my spouse visa to be approved – something we had to apply and pay for only a couple months after receiving the costly fiancee visa. But it came that summer. And I held my first UK job after many, many, many rejections. I found taking my spouse’s Anglicised surname proved more successful.

I also found that I took growing up in New Jersey for granted. Nestled between New York City and Philadelphia, New Jersey is one of the most diverse places on the planet. I grew up with friends and classmates from all around the world – most of them second or first-generation Americans like myself. When you were asked, “Where are you from?” It was followed by a compliment.

So imagine my shock, in my first job at a bookstore retailer where one of my first customers says, “I don’t want her serving me – she’s a foreigner” and furthermore, when my colleagues stepped in to serve him. No one stood up for me or thought anything of it. I excused myself and broke down in tears only for my manager to remark, “That’s what you get for hiring so many women” to himself.

I didn’t understand why the subsequent jobs after that (cinema, craft store, newspaper, radio station, private schools, after-school clubs) echoed this same job-stealing sentiment, but the British stiff upper-lip was far more bewildering. Friends and family downplayed my experiences. Their histories, interests, and friendships remained within the city – to them, this sort of thing didn’t happen. “There’s ice cream in the fridge.” When you were asked, “Where are you from?” It was followed by an insult.

I saw my friends and family again in 2015 for our second wedding (“the real one” in which we could actually decide things). It brought together our many friends from university, our families, and some of my stateside friends. I remember “springing back to life” in their company – and “withering” upon their departure. I always thought my best friend would be my maid of honour – but she wasn’t. She couldn’t come. She became a mom.

I went into a very dark and insular period of time after the wedding and it lingered throughout 2016. I could not afford to visit home because I had to save up for the next step – the 2.5 year mark. I started fantasising about a new start somewhere else. Like Berlin or Amsterdam or Ireland.

During this time, I worked for one of the lowest-rated schools in the county and right away noticed the discrepancy between demand and supply. Overstretched, underpaid staff. Invisible, vulnerable, at-risk students hidden in plain sight. Absent safeguarding leads. Teachers who couldn’t spell, teaching students who couldn’t read. A broken system concerned only with exams results.

Students confided in me, an emotion-detecting receptionist over their teachers. Their parents came in, wearing ‘Vote Leave’ pins, demanding forms for free school lunches and assistance in filling them out. Then they threatened my life because their child was facing expulsion for threatening another student’s life. They always demanded to speak with a nurse or a police constable – but they were very rarely there.

I didn’t believe it when I woke up to a different UK. One that voted leave despite a hostile campaign. Moreover, I couldn’t believe people my husband actually knew voted that way – given they knew what we were going through. They argued I was a “good immigrant”.

The very first place where I interned as a student in 2009 made national headlines when it was vandalised. The shop down my road went up in flames. I realised what I was experiencing was very real. And I saw it among colleagues, customers, friends and family. I learned this intentional cruelty was encouraged by the government.

I saw also the paper hearts in the window of that burnt, boarded building. And the condemnation of those vandals in London. I stood in a small rally – maybe two or three rows thick – listening to speakers share stories like mine, and feeling solidarity with them. After three years, my pain validated for the first time.

Still, I wanted to go home – I’d reached my breaking point of Theresa May’s strong and stable hostile environment. And now, after David Cameron’s dooby-doo, she was Prime Minister. But home wasn’t safe anymore. Obama gave way to Trump and with him a hypocritical tide of flag-waving hatred. It was Hilary and the Democratic Party’s fault, too. They were afraid of Bernie Sanders and his much-needed movement for systematic change.

Gone was Berlin, Amsterdam and Ireland. We moved into our first flat together – and made it a safe harbour from the outside world with David Bowie, Chris Cornell, Chester Bennington, Anthony Bourdain, Black Mirror, Game of Thrones and Mr Robot.

My husband “went places”. My depression didn’t. I reached out to doctors for my insomnia, who would confide in me that they did not like living here and were thinking about leaving – and that the wait for mental health treatment could be be up to six months.

Not long after, I read an article about the Home Office asking GP practitioners to help them deport migrants with mental health issues. I cancelled my appointment and called a friend instead. But he’d just lost his brother to the heroin crisis that claimed our hometown – once the safest city in America.

On the cusp of 2017, I applied for further leave to remain, was visited by family for the holidays, and started a new job at a college. The Home Office did not help me prove to my employer that I was allowed to continue working as my further leave to remain application and status were being decided – even though I could show it to them in the appendices on the UK government website. This caused me considerable financial stress. I had to save for either scenario – being rejected or the next stage (indefinite leave to remain after another 2.5 years) – and my job was at risk.

In addition to this, I was paying student loans to US servicers, which would not accept payment directly from my UK bank account. I had to pay expensive transfer fees each month. This meant any time the Conservatives – or Trump – did or said something stupid, I literally paid for it. I also had to file taxes (£400) to the IRS (if you are American it doesn’t matter where you live, you still have to file taxes – even if you don’t owe the IRS anything).

Lo and behold, the letter came on the brink of being let go. But the card didn’t. The £3,000 card that I applied for was not attached to the letter. I had to write to the Home Office to remind them of this.

Stateside friends visited us in 2017 – a drummer who I was in a ska band with and his soon-to-be-fiancee. Both reported to me they had been interrogated about my relationship with my husband at the airport before being let through the border agency. Their visit made me realise how different and bitter I had become – and how this Anglicised version of me wasn’t actually me. It was the beginning of a necessary U-Turn. “It’s so beautiful here,” my friend’s fiancee said. “That’s because you don’t live here,” I replied.

My family visited. I learned that my autistic sister was suffering at the incompetence of the Division of Developmental Disabilities, and my mother was suffering from prioritising turning up to work to pay for the mortgage over her own deteriorating health – and having to choose between having one utility over the other every month. Meanwhile, my father, in his retired isolation with two small kids, was barely living on social security amid Duerte’s death squads. They wanted my help, but I couldn’t help them because I couldn’t even help myself. I turned to music. Royksopp, Radiohead, Thursday, Gorillaz, Cog, Nine Inch Nails, PUP, A Tribe Called Quest, Fever Ray and Lauryn Hill.

One day, a student came to me, visibly stressed about the Home Office wanting him to verify his attendance at the college where I worked. I told him I understood and said I would make sure the secretaries knew it was extremely important and deserved priority. They did not like being told what to do, especially from a mixed-race American, and complained about me to my manager.

When the student came back for the letter, the secretaries told me they knew nothing about it and there was nothing they could do. I could see the stress in that student’s eyes. Wide and filling with tears. Their empty hands shook. They left the school and probably the world that day. I put in my notice.

In my last days at the college, I took many calls from parents asking for their sons and daughters to be removed from the register because they took their own lives. This followed notices for missing young people. This followed little support offered to students and the little to no regard for their safeguarding and wellbeing. This followed reports of no jobs, no social mobility, no future.

This followed students asking the finance department for lunch money, for bus money – only to miss the last bus at 4 pm, even after ducking out of class early to catch it, and now needed money for a taxi across the county.

This followed students getting expelled for not being able to get to class and having their bursaries frozen and losing their housing and needing to talk to someone about it, only to be told to get an ice cream with a condescending voucher.

On my thirtieth birthday, I arranged a reunion. Friends from university. Local friends. Work friends. In-laws. I’d finally found myself. It was worth celebrating. Now, with just a year and a half to go before the next application, including a Life in the UK Test, I had to figure out where I belonged. But it snowed – worse than New Jersey. A blizzard that covered all of the UK.

I couldn’t help but think of my first friend in the UK every time I read a headline between what was happening in Trump’s America and what was happening in Tories’ Britain. His birthday, the week after mine. I thought, maybe, being respectable thirty-year-olds, we could – and should – forgive our twenties.

I went to wish him happy birthday on Facebook, only to find out he was dead. And had been dead. For three years. It was a pain I’d never felt before. I wanted to tell him I was sorry and that I was stupid and wanted to trade places with him. My only hint was he was depressed for some time living in Spain and his death was quick. He was only twenty-seven years old. I obsessed over his last posts a lot:

1. Bernie 2016

2. “It’s Not Worth It” by Linds Redding

3. Well done Great Britain, you’ve really fucked yourself this time. Glad I won’t be around to see it (in reaction to the Conservatives winning in 2015).

I went home for the first time since 2014 in 2018. I cried at the New York City skyline and appreciated the tristate area I used to complain about in another life. No one stared at me because of the way I looked or the way that I talked. Clothes actually fit. People actually spoke their mind. I spoke without an accent.

We talked about our little, dark, transatlantic age. We walked the rebuilt boardwalk and went on a road trip to a wedding. It was home – but it also wasn’t. Maybe things change simply because the people are gone. My drummer friend married his fiancee, scored a high-flying job that graced the pages of Forbes and bought a house.

My next job, working for a youth charity, showed me, first-hand the effects of austerity under the Conservatives. Cuts to public services. Unemployment. Homelessness. A reliance upon food banks. A dependence upon abusive providers. Lack of jobs. Lack of transportation. Lack of social mobility. Reduced police. Reduced NHS. Anxiety. Depression. A suicide crisis worsened by two-year waits for help. Corrupt charities and their trustees. Skewed statistics. Special measures. I wanted to help young people live. But the system had many holes and they slipped right through.

My post ended. I returned to writing about music for a little while, but found the music scene was suffering because of gentrification. I found the shops in my neighbourhood were fighting to stay open because of gentrification. I found the community in my neighbourhood being stamped out because of gentrification.

I learned the wedding road trip we went on resulted in the skin cancer of my stateside bassist friend’s newlywed wife. I also learned that they were pregnant. And they were struggling to pay for it all despite working overtime.

I went to Wales to say goodbye to my first friend. I walked up that slanted, terraced street, past his house, and up into the forest. Most of the trees were gone and replaced with wind turbines. I got lost, but ended up at the cemetery.

It was weird to be looking up at the mountain from his grave. I stayed in the only “hotel” in the town. I now understood what he meant about living there. I understood what it was like to get away and live in London. And then not be able to afford it anymore. I could also sympathise with his final days. What it’s like to live in another country and not belong there – only to find you don’t belong home anymore either.

Later, I found myself on the Snowdon mountain railway with an enamoured American student who was on holiday with her British boyfriend, revelling in being exotic. Not a single grey hair. Not a single black circle. Not a single clue of the path ahead of them.

When I came back to Norwich, I got involved in a documentary indirectly about the impact of austerity on the mental health crisis in Norfolk. I thought it fitting since my friend was a DOP and loved making and watching documentaries. The stories reflected my experiences.

I took my pub quiz-style Life in the UK test. I felt I got every single question right. I celebrated Theresa May’s resignation. But I still lived out of a suitcase.

I walked the North Norfolk Coastal Path with my husband in a heatwave that made the marsh look a dry desert and the coast a stretch of hot coals. Everyone made a fuss about the temperatures – temperatures I was used to back in New Jersey. They said it “didn’t really get that hot” and it was “pretty rare” to swim in the North Sea. Everywhere we went, everyone was talking about their disappointment in Boris Johnson’s ascension to Prime Minister.

When I got back, my drummer friend’s wife told me her husband was now miserable in his high-flying job and trapped there with a mortgage – and he wasn’t talking. I wanted to meet him whilst he was doing business in London, but he had a tight schedule.

I remember walking around Oxford Street without being pushed and pulled. I remember overhearing offensive remarks in the English tongue. I remember revisiting all my favourite places to find they were all shut. And that no one lived here anymore. And that it was quiet. A ghost town full of British chains and let signs.

A homeless nineteen-year-old asked me, a once homeless nineteen-year-old, for change. The bridges of my twenties, now covered in signs trying to persuade you not to jump between the scaffolded sight of Big Ben and the sneering Bank of England.

One of my husband’s last remaining friends, who lived all but one, infantile year of his entire life applied for British citizenship, chose to remain in the UK and open his business with his European partner despite “get Brexit done”.

I watched Norwich fight against gentrification with new music venues, pollution with zero-waste shops, isolation with inclusive, community-centred events and social groups, ignorance with history, cuts with charity, and hatred with love. I lost track of time. My best friend’s baby turned four years old and started school. She called me “auntie” despite me never having met her.

I submitted my application for indefinite leave to remain status in August of 2019. We prepared for citizenship, for appeal, and for denial of appeal. We journeyed just over sixty miles to my biometrics appointment because our local centre was open for three hours a week – across three days – with no openings. It took place in a library with a privacy curtain. The whole thing took about fifteen minutes, and was done on a ramshackle Dell set-up. All I had to do was trip on a wire to lose my file. On top of that, I paid £80 for them to scan my files – but ended up scanning it myself.

I regrettably backed out of being a bridesmaid in a wedding because it made me think of my own – and how bitter I was about weddings – all weddings – thanks to the Home Office. I got married five years ago and was still – still – fighting for my marriage.

I waited for the decision. Game of Thrones got everyone angry. The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance made up for it. So did Good Omens and Fahrenheit 11/9. Bernie Sanders returned and brought a bigger movement with him. People like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ihan Omar, Rashida Tlaib and Greta Thunberg happened, bringing a movement with them. It rippled out to my own neighbourhood. Worldwide protests. The global demand for change. Boris Johnson prorogued Parliament and got challenged up and down the country by the will of the people. I joined a packed rally in the city and couldn’t move. Brexit didn’t happen on 31 October. Trump’s impeachment trials finally did. An office landlord finally installed a fire door. Another one finally installed a shower – and received my £4,000 indefinite leave to remain status card in the post without having to sign for it.

It’s all coming to a head in 2020. The fate-defining year for all humanity. Get it wrong and it’s game over. There’s no time for a second chance. Bernie Sanders might win the election. The Conservatives might lose. There might be a second referendum. There might be revolutionary, radical, transformative systematic change. A re-haul. A re-set. A better life for my friends and family. A future for their children and grandchildren. Maybe. Just maybe.

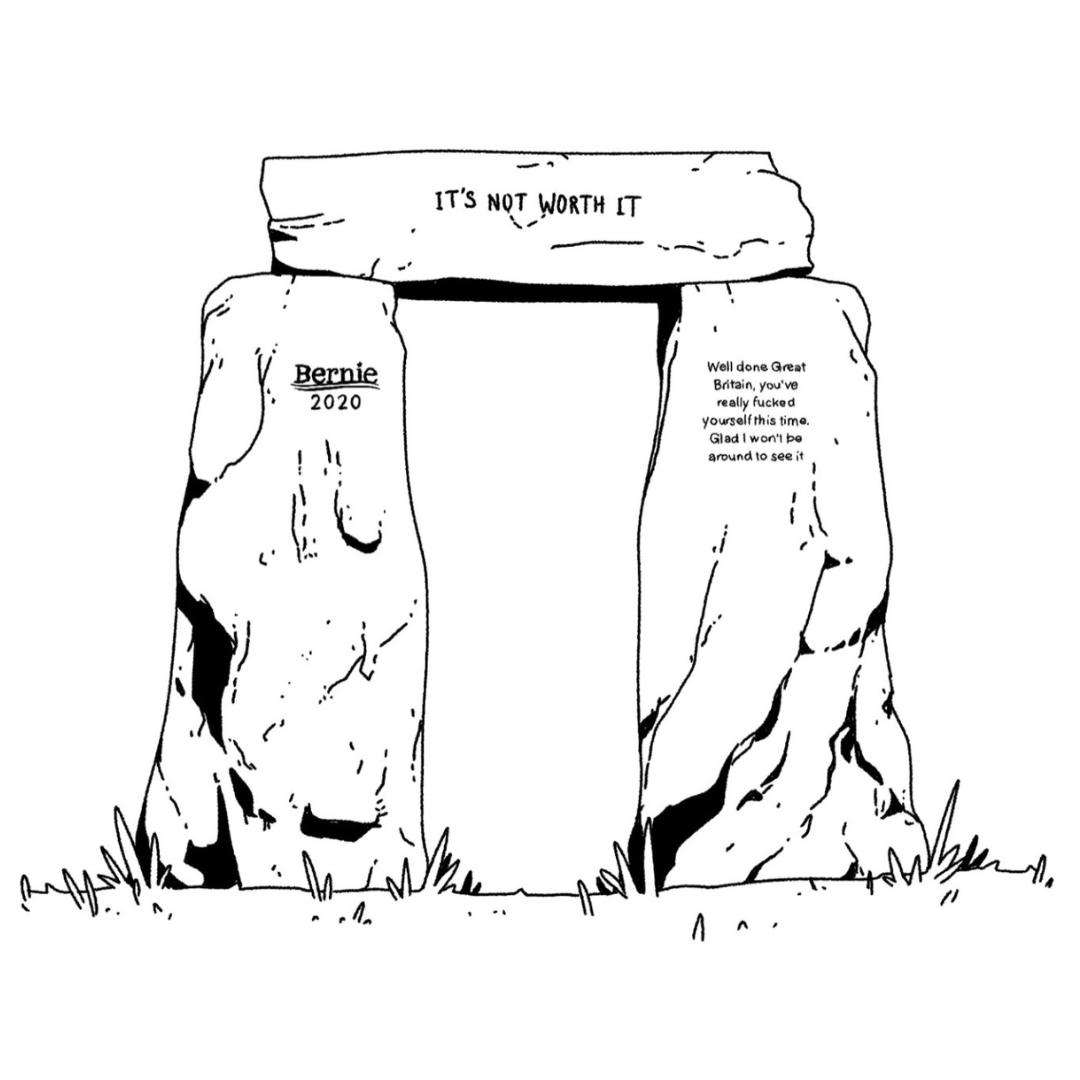

If not, maybe we can do one final act of kindness and leave behind a cautionary Stonehenge of our own for the extraterrestrial archeologists to study and learn from in 2030. Maybe inscribed with:

1. Bernie 2020

2. “It’s Not Worth It” by Linds Redding

3. Well done Great Britain, you’ve really fucked yourself this time. Glad I won’t be around to see it (in reaction to the Conservatives winning in 2019).